Ande and I turned the corner on Nepkoztarsasag Utca, Avenue of The Republic, toward the Heroes Plaza. Billowy clouds punctuated a clear warm Budapest morning.

We were clad in black except for identical swatches of Hungarian red, white and green on our jacket lapels. Margit had performed the honors, completing the ensemble with a thin ribbon of mourning black around each tricolor. With my set was a pin of Nagy Imre; with his a button marked FIDESZ for one of the country’s leading opposition groups. In Ande’s finest English he turned to me and said, “This day is history.”

I had arrived tight on the platform at Keleti Station five days before this long overdue service for Hungary’s unforgotten dead. Hailing a cab outside the grandiose Eiffel-designed train terminal, my first stop was the Orszaghaz Borozo, a medieval wine cellar in a section of Budapest dating back 1,000 years. My expatriate Hungarian roommate in Boston assured me this was an excellent spot to view patrons enjoying a nationalist song or two. What better place, I thought, to begin my look at arguably East Europe’s most independent state, a state on the verge of breaking out.

Things were changing here. And changing fast. Last year the Communist Party ousted the late Janos Kadar from its top leadership post, a position he held with Soviet backing since the failed 1956 uprising. Kadar was replaced with a centrist who in turn has been largely stripped of power in favor of party reformers. Moreover, agreements are in place to hold parliamentary elections this year or next. In the spring tens of thousands marched peacefully in the formerly discouraged commemoration of the important 1848 revolution. Attendance at the government’s official ceremonies paled by comparison.

And now the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party had lifted its ban on public recognition of June 16—our big day—for former Prime Minister Nagy Imre. It was Nagy who led the short-lived 1956 uprising which Soviet tanks and soldiers smashed in days against virtually unarmed civilians. In the aftermath, Nagy and four colleagues were arrested, condemned in a show trial and hung — an old Hungarian tradition — on June 16, 1958. Their remains were tossed into an unmarked grave known only to party officials. Thirty-one years after their demise Nagy and his followers would finally receive a public funeral. It was this event that brought me here.

Coverage of these recent doings was widespread in the Western press, and I was not one to overlook it or the opportunities they offered. Poland — which only days before my arrival held the first open elections in East Europe since the late 1940s — and Hungary were permanently altering the bloc’s status quo. These changes already outpaced their inspiration in the Soviet Union, President Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost. From where I stood, the unprecedented nature of Nagy’s funeral lay in the wide field of reactions, albeit risky ones, presented to Hungarian society; from open, unfettered rage at its Communist Party and the Russians to dignified reverence for a national legend. To say this country of 10.6 million people faced an uncertain future was an understatement.

My immediate future lay in the hands of 23-year-old university student Kiss Endre. Endre, Ande for short, is an old friend of my friend and roommate Miko Sandor. Sandor contacted Ande as I formulated my plans in Boston, and he graciously agreed to be my host at his mid-town three-room flat. Ande shared the tastefully appointed quarters at 54 Rozsa Ferenc with his grandmother Margit. We met that Sunday evening after sampling the ample treasures of Orszaghaz Borozo. Unfortunately I don’t recall whether or not I was the only one singing. And I learned my first in-country Hungarian word, egeszsegere. Cheers!

Monday through Thursday I spent viewing the sites, taking in clubs, hanging with Ande’s friends and relatives, eating and drinking well. Anything but conventional, I came to Budapest with an idea of observing the recent happenings through the eyes of ordinary people, not someone like government officials or whatnot who might tell me what I could get myself.

On Thursday Nagy’s ceremony dominated the evening newscasts. Communities throughout the country were openly remembering the dead of ’56. One spot highlighted Sopron, the prime minister’s hometown. Ande and Margit watched the coverage intently. Near the end of the broadcast Ande went into the kitchen while Margit walked over to the tall bureau near my chair. Reaching high she didn’t look at me or say a word. Her hand came down with a single match and I looked to the window.

That evening and Friday, supporters of the revolution lit window candles in memory of the casualties. Margit already had a candle atop a decorated base in the appropriate spot. I knew her intentions the second I heard the matchbox rattle. Margit sauntered purposefully to the candle; the wick caught and she turned to face the kitchen. Ande walked in and his grandmother motioned to the new flame. He looked at me and smiled.

During the street fighting three decades ago Margit kept inside, protecting her two children. Ande translated in broken English and conversational German that she remembered the time well, especially the sight of a ruined Red Army tank. When I asked what she thought of The Party, a strong right foot booted a crisp arc as if kicking it out the door. Still, an appearance of calm determination graced Margit’s face in her brief and personal ceremony. I saw no lasting bitterness or rage.

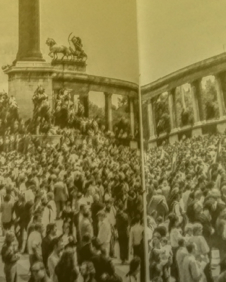

It was shortly after 10:30 Friday morning as we entered the Heroes Plaza in our formal black among a growing throng of pedestrians. “Jesus! Look at all these people. This sure is history,” I declared to no one as we crossed Dozsa Gyorgy Avenue near the Yugoslavian Embassy. Now I got excited. The plaza side in front of the specially decorated Art Gallery building was packed with thousands.

My attention went to center square where scores of people were on and around the bronze horsemounted Magyar chieftains at the base of the tall Millennium Monument. The spectacle of these people, their colors and flags created a jumble of life in marked contrast to the long black shroud draped around the monument’s single column rising above them.

“Over here!,” Ande shouted, gesturing to one of a handful of crane-like camera booms dotting the plaza. I scrambled up the truck-size base with Ande’s help to get photos of the overall crowd. What I saw was massive. The scene reminded me of pre-massacre photos of Tiananmen Square.

A long, elevated stage for the international press corps made it difficult for people on the ground to see the coffins laying in state among the remodeled Gallery steps. Nagy Imre’s coffin, however, was centered and raised above the others: Gimes Miklos, Szilagyi Jozsef, Losonczy Geza, Maleter Pal, and a coffin representing all the other dead. A huge burnished gold receptacle cradled a memorial flame while lit torch stands needled the aisles between the remains. Above and to the right of this pageantry hung a long white triangular banner sporting a circular hole at its widest end. The hole had been scorched by fire. I took this to be a symbolic link to the revolutionary flags of ’56 when rebels cut out the circular hammer and sickle insignia superimposed on the red, white and green by the Communist takeover.

The entire dais, building columns and classic portico were covered in black. All over Budapest black flags and the national colors flew side by side on schools, office and residential buildings. Finished, I got off the boom and we walked closer.

Hungarian banners and flags of all ages waved in the breeze among the crowd. A few bore names of towns. One foreign banner was very conspicuous, SOLIDARNOSC. Solidarity there confirmed to me that this intimately national funeral held a lot of import to the rest of East Europe.

At 12:30 p.m. our plaza along with the nation observed a moment of silence for the Prime Minister. Nearly an hour of speeches followed. Shortly before, I spoke with two Hungarians who knew English. I asked 31-year-old teacher Feher Judit if she ever thought a day like this was possible: “No. No, I did not even dare to hope, to think of it a year ago. No one, I think. Then quite a few things changed.”

A professional man in his mid- to late-thirties told me he attended a far different Nagy commemoration in 1988: “I was at Szabadsag Square exactly one year ago. It was illegal and police came, and they hit people with, as we call them, ‘Kadar Sausage.’ ”

Now the assembled people were free to remember and listen. Through it all they remained attentive and for the most part reserved. At midpoint, however, everyone burst into the Magyar Himnusz, the national anthemn. “ISTEN ALDMEG A MAGYART! —God Bless the Hungarians!” This moment was a big reason I came; to experience the collectively voiced aspirations of a united people.

Ande sang with little visible emotion though I detected a strong inner pride. “HOZREA VIG ESZTENDOT! — Bring them a Happier New Year!” I saw a lot of emotion on many faces. One woman behind me sang with a conviction I cannot forget. We also sang a religious hymn with similar results in this officially atheist nation.

Minutes later there was an announcement and Ande took my hand. Then the entire plaza joined together, and we began to recite names, names of the revolution’s dead. Concentrating on Ande’s voice I struggled to do my best. When it was over, he said to me “Never again. Never again.”

“Nagy Imre!” Ande declared, motioning with his head to the stage as a scratchy voice came over the loudspeaker. It was a recording of the Prime Minister’s radio broadcast to the nation four days into the uprising. The plea to his countrymen included the now sadly foreboding words “Bring back the trust of the people. Don’t let brothers’ blood run in the country.”

Orban Victor, speaker of FIDESZ, The Alliance of Young Democrats, gave the final speech. His oration received the greatest applause. Whether it was Orban’s words or Ande’s thoughts, he translated “Soviets out!” Did he mean bazd meg (expletive) the Soviets? “No,” Ande replied, “only Soviets out. A hard speech. Very hard!”

The funeral’s public wake ended after Orban. Soon Nagy and the others were taken to private graveside services at Rakoskereszturi Cemetery. Both plaza and cemetery services were broadcast live on state television.

Ande led me from the plaza back down Nepkoztarsasag Utca. People jammed the sidewalks as we made our way home. I went up on a raised area to get a better view and snap off some last photos. A moving sea of humanity is the only way to describe it. Radio Budapest estimated the crowd at 250,000.

Back at the flat Ande and I had a bite to eat before retiring to his room. The clock showed almost 2:00 but the day seemed hours older. Margit had the television turned loud to the burial ceremonies that lasted until early evening.

Ande came up with a bottle of white wine and poured out two glasses. We raised our drinks for a toast. “Nagy Imre!” Ande said. “Egeszsegere!” I replied.

Appeared in Quimby Magazine, 1989.

Photo by LJM.