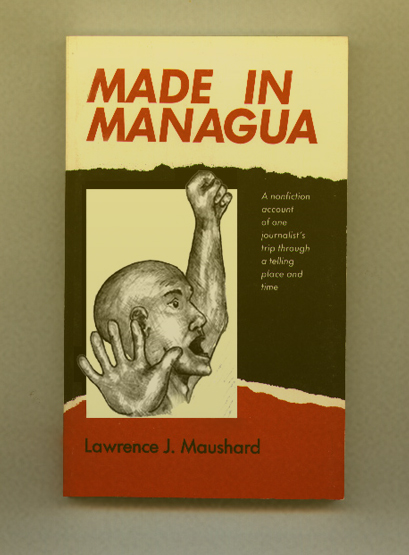

MADE IN MANAGUA

Chapter 19

Today’s La Prensa has a front page story announcing a Grand March of Workers for Sunday morning at the Plaza Ana Maria. I’ve seen posters in the city advertising the event, and it seems like there may be a big crowd. But La Prensa’s story is more than an announcement: it is an exhortation to attend, something akin to old Bolshevik posters urging Workers! Soldiers! Peasants! and Students! to Unite for the Nation! This is supposed to be a newspaper? My crude translations are enough to tell me that journalism in Nicaragua is played by a different set of rules.

On my way home from the cathedral, I share a taxi with a Rastafarian. His dreadlocks are awesome. I have no idea how common Rastafarians are in Managua, but he stands out for me. A gringo and a Rasta tooling through the streets of the capital: an odd couple indeed. When I try to make conversation, he asks if I’m C.I.A. “No,” I answer with a laugh. He’s the first person in Nicaragua to link me with any unsavory image. In fact, I’d prepared myself to be a target of unending anti-American vitriol. Who else but the Nicaraguans had more right to hate Americans these days? But no one has shown me the least bit antipathy, slight or malice. And it’s not like there’s a lack of anti-Yankee propaganda. I saw one billboard near the cathedral displaying a machine gunning soldier and words about Estados Unidos and Invasion.

For the other side of the coin, I have only to turn to Donald. During one of our increasingly high-pitched arguments, he says that people here are “waiting for the invasion. They want the invasion to come!”

Grenada has come and gone but Reagan has no guts for an invasion here. Not with U.S. troops. There could be no quick and easy victory. Hell, they nearly bungled Grenada, the tiny island most people couldn’t find on a map if they tried.

“There isn’t going to be an invasion, Donald. I know that. The American people won’t let it happen. If you want the Sandinistas out, you’ll have to do it yourself.”

Driving through a shattered mid-town neighborhood on the way to a market, I see that the business and residential streets here are separated from the marketgrounds by an open dump. It might have been the earthquake, now 15 years ago; it might have been the incessant poverty infecting any urban center. But this place was an open sore that words and ideologies and guns will never heal. It needs real action. Desperate action. And here’s Donald telling me the people want an invasion. Yeah, that’s just what they need.

My big rally is less than a week away. I’m not yet sure of the time, but the date is set for Thursday, November 5, at the Plaza de la Revolucion. For now, things are moving at the right speed.

Saturday’s no big deal. Spend my time wandering the markets and streets. Meet my first Nicaraguan Communist at Roberto Huembes Market selling party flyers that aren’t very interesting. He tells me in halting English how the Sandinistas aren’t Communists at all. The state, for example, does not own all the factories and the other means of production. The Sandinistas are, he insists, nothing but capitalists. Capitalists?

The streets I walk do nothing to alter my grim view of the city: block after block of Sandino graffiti and political slogans. And from what I see, the majority of shops that do have business signs have some kind of connection to autos, trucks or motor parts. Like a junkyard strip in a seedy Midwest village or the waterfront in an oily East Coast hamlet.

In the crowded streets and squares armed soldiers are everywhere though they don’t seem to be on active patrol or other official business. I never see them stop or question anyone. No glaring stares either. Passersby pay them no attention. Guns in the streets make me uneasy only in the manner with which they carry their weapons — with a casual flair, rifle barrels pointed waisthigh. I hope to God these people are well trained.

The next morning I’m outside the Huembes Market again, at the Plaza Ana Maria. Looks like a basketball court to me. Organizers are beginning to set up by 8:30, and I notice a large number of red flags being unloaded from a van. Workers are handling about a dozen bloodred flags highlighted with the hammer and sickle. I pull out a few thousand cordobas and try to buy one, a Nicaraguan Communist Party banner. But the guy won’t bite. Wonder what he’d have done for a $10 bill? Unfortunately my American cash is back at the house. This brief spectacle only reinforces my notion that we had a poor idea back in the States about what’s happening here. I mean, the Nicaraguan Communists are ready to march in opposition to the Sandinistas!

A lot of photographers and notebook-toting reporters are cruising around. One photographer catches my eye — blonde Caucasian woman in safari shorts. I make it a point to get close.

“Who are you working for?”

“U.S. News & World Report. I’ve been shooting in and around Managua for the past few days. And you?”

“Freelance. Came down from Boston about a week ago. My name’s Larry.”

“Candace. I live in San Francisco, but used to in Boston. Still know some people there. So you’re writing freelance?” she asks, looking at my notebook.

“Yeah. My main interest is the rally on Thursday about the Arias plan. Should be a big deal. Otherwise I’m just trying to find out what I can.”

“You came all the way from Boston to do a story on a rally? Freelance? That’s, ah, ambitious.”

“Yeah. I mean, it’s important and I’m interested.”

For the moment I’m more interested in Candace. Attractive and my age.

“Where are you staying? The Intercontinental was full up so I took this room at a place way on the other side of town. It’s not so hot. Not a restaurant or anything decent around.”

“I ran into this Nicaraguan who knows English, used to live in the States. He invited me to stay at his home. I got real lucky, I guess.”

“Have you had anything to eat?”

“No. Not really. But I know there’s vendors in the market. Right over in that building.” I point back to the place where I’d dined several times.

“Yeah. But they probably don’t have anything vegetarian, do they? I don’t eat meat.”

“I have no idea,” and think what a strange, out-of-place notion. People who can’t get enough to eat all over and she’s worried about tofu.

“Well, I’ll go check it out. Doesn’t seem like anything’s gonna happen for a while.”

“Nice talking to you, Candace. Take it easy.”

“Bye.”

Melodramatic scenes of the beautiful photographer and the daring journalist spending passionate evenings in Managua momentarily dance through my head.

More people are filing into the plaza. But many in the area have other things to do than protest. A group larger than those in the main plaza are queued up about 30 yards off in a bus terminal.

About 9:00 the attending groups — mostly labor unions and opposition parties — begin massing around their banners. Some pose for photographers. Others try to outshout everyone near them for the attention of anyone who’ll listen. The biggest group wears pink paper sun visors. Pink. All this chanting and posing goes on for an hour. One guy gives a speech.

At 10:00 the entire plaza suddenly takes to the street. We walk out to a main highway, spread out the width of the road, and march. The sun is already merciless, but plenty of drink and ice carts tag along. Those enterprising vendors: doesn’t matter who’s doing what. If there’s a crowd, sell ‘em something.

From the beginning I keep to the sides of the crowd, trying to get a wide-angle view. Photographers are madly dashing about, trying to stay in front of and above the crowd. I can occasionally see Candace out there, ripping off shot after shot. All the while I try to stay within eyesight of a man in jeans who had been pointed out to me as a Nicaraguan Communist Party deputy. Back at the plaza, a Brazilian reporter filled me in on a few things, including a statement that the local commies are a rightist group. Maybe something got lost in the translation, but that’s what he said. Anyway, the Brazilian points out this party deputy and I keep him in sight. For what reason, I can’t say.

I will say one thing about the Communists. Their red flags hands down make the most striking visual image in the march. Broad swatches of crimson red amid the sea of white and muted pastels. The entire crowd looks to be 2,000 or 3,000 strong.

Along the road I see one cabbie, on the other roadside, thrust up an arm in support of the march. A pedestrian does likewise. And I see lots of handshakes between marchers and onlookers. After a short time the marchers turn off the wide highway into a narrow residential street. Many people poke their heads out doorways or stand and look as the marchers walk by. Some even cheer. But as far as I can see, there is no sign of wholehearted public support.

An hour into the march, I’m getting tired of the walk. That’s all it is, an unending protest march through the streets, except for a few times when we stop and someone makes a speech. But I figure there’s nothing else going on. And something may happen. Then I run into a middle-aged white man looking very much out of place. Turns out he’s a reporter for the San Diego Union.

“You’re really smart to have worn that hat. I can’t believe this sun,” the balding, unprotected reporter says after I introduce myself. From Comiskey Park to the river landing in St. Louis, to the dirty streets of Managua, that ChiSox cap has done me good.

“Yeah, I guess so.” I can’t keep my information a secret and tell him about the party deputy.

“You speak Spanish, Larry?”

“No.”

The reporter walks up to the guy and talks with him for several blocks. I feel shortchanged, walking behind this drip who’s doing the interview I should. When he finally drops back a few steps he says the deputy claims the commies are marching over “bread and butter” issues.

Two hours into the march. Most of the people, unlike me, don’t seem winded. Sandinista police are shadowing our parade but they’re not out in force. One or two around if you make the effort to look.

Back into the business district, me on the sidewalk, I see this neatly dressed man bolt from crowd central with a tape recorder in hand, being chased by two or three others. Running for all he’s worth, the guy darts past me to my left and down the street. My first reaction is he’s stolen the recorder. But that doesn’t jive. Why would a guy dressed like him do something like that? About 25 yards behind me, the pursuers catch up and pin the runner against a wall. Then a horde of people, including photographers, swarm in. It’s a melée, and I see the runner getting punched. Should I go over? Wish I had a camera! But I don’t go. Must be the violence. It’s all over in minutes, and I trot off with the rest.

On Monday El Nuevo Diario runs a screaming headline about the attack, accompanied by three photos. I wasn’t in any. Whoever took the pictures had been fast or lucky or both. Two stills have the runner in full flight. Turns out the guy is a reporter for Voice of Nicaragua radio who had been interviewing the head of the local Communist Party. The interviewee reportedly got angry when questioned about the presence of American officials in the march and the rumored U.S. Embassy support of other anti-government activities. The Communist official reportedly got so incensed that he attacked the reporter who then ran off, right past me. I wonder if the local press knew the commie was a hothead and figured they might get a rise out of him.

La Prensa only mentions the incident at the bottom of its march story. The headline blares out that 20,000 people attended. El Nuevo Diario claims 3,000. A cop estimated 3,000 to the San Diego reporter, while a march leader I heard claimed 10,000 to 15,000.

Whatever the numbers, it appears that the government-line press — as well as La Prensa which claimed its people were roughed up at El Calvario — now has its own example of opposition “attacks.”[]

——————————————————-

Made in Managua: a nonfiction account of one journalist’s trip through a telling place & time

Published by Quimby Archives, Boston 1990. ISBN 0-9626912-0-8. Original illustrations by Tim Gallivan. Cover drawing by Miko Sandor. Cover design & page layout by Ian McConnell.

Reviews

Journalist Experiences Nicaragua After Dark: Irreverent Account of Shell-Shocked Society by P. Gregory Maravilla.

The Harvard Crimson

Rarely can Americans fathom what goes on outside the United States. Maybe the widespread poverty and violence in American cities approximate the conditions of poor, war-torn Third World countries, but the conflict we see at home will always be the conflict of a rich society.

When American journalists make the occasional sojourn into the world beyond our borders, they are usually insulated from harm and produce relatively mild accounts of their trips. One such trek has given Lawrence J. Maushard the material for his new book, Made in Managua.

Seen through the eyes of a liberal white American, Made in Managua is a memoir of Maushard’s nonchalant exploration of Nicaragua at the end of its civil war. The book does not attempt to relate the experiences of the war-torn citizens of Managua, but Maushard does succeed within his limited scope — he gives a superb fresh-out-of-college journalist’s depiction of his jaunt through North America’s most bitter war zone.

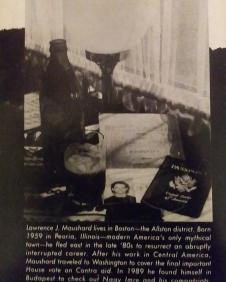

Maushard embarks from Boston in his “beast,” a dilapidated car that takes him to southern Mexico. His $900 already wearing thin, Maushard makes a valuable friendship with a Nicaraguan franchise operator, Donald, who helps him to the Nicaraguan border. The acquaintance really pays off when this wealthy merchant provides Maushard with the food, shelter and information he needs to survive in Nicaragua’s capital city.

The author plays the whole journey by ear; he frequently does not know where he will stay or where his next meal will come from. This lackadaisical attitude drowns out any political insights that Maushard might have gleaned from the trip. Instead, he dwells on satisfying his primal urges for women and devotes considerable effort to describing each one he encounters.

When he is not smoking pot, drinking and “getting laid,” Maushard manages to scratch the surface of a Nicaraguan culture scarred by civil war. The people he encounters and the protests he witnesses produce an unsettling ambiguity about who is the hero and who the villain in the jumble of Nicaraguan society.

Maushard originally set out for Central America as a freelance journalist to cover the announcement of the Arias Peace Plan in Managua. While this pedestrian premise may disappoint Hemingway idealists and leave Michener mavericks unsatisfied, the book gives a surprisingly novel and realistic perspective of Nicaragua — albeit from the viewpoint of a privileged, aging hippie.

Maushard triumphs for precisely this reason: he makes no pretense of providing a masterpiece of literature. He recounts an adventure, a personal involvement.

Made in Managua offers a simple, contemporary account of a single American’s brief encounter with the tumult of Central American politics. Maushard effectively provides us with an unpolished, but rewarding portrait of Nicaragua. Although his brief account is not particularly insightful, it paints a memorable picture of something most Americans will never know. (1991)

He was there: Peoria native has an adventure in Contraland

by Bryan Oberle. Peoria Journal Star

From New York Times reporter Harrison Salisbury’s extraordinary visit to Hanoi during the Vietnam War, to Hunter S. Thompson’s hilarious and insightful tales of the 1972 presidential campaign, first-person journalistic accounts have a long and rich history in American literature.

Made in Managua, a paperback book by Peoria native Lawrence J. Maushard about a trip to Nicaragua during the Contra war, is a limited but somewhat successful attempt at this sort of reporting.

Maushard, 31, a graduate of the Academy of Our Lady/Spalding Institute and Illinois State University, has written a frank book.

He candidly says that his reasons for going to Nicaragua were job misfortune and boredom. After starting his journalistic career at the Pana-News Palladium, Maushard lost his job at the Pekin Daily Times when a drunken-driving charge cost him his license.

“My journalism career needed some hard fix in a bad way,” Maushard writes. “Plus, I figured if James Wood (in the film Salvador) could drive to and return from that Salvadoran hellhole, I could make out at least as well in lukewarm Nicaragua. Let’s face it, the Sandinistas got all the street fighting done years ago.”

In October 198(7), Maushard left a warehouse job in Boston and set out for Nicaragua in his 1975 Nova with $900.

His primary aim was to be on hand when the Sandinistas made a formal response to Costa Rican President Oscar Arias’ peace accords, the first step toward ending the Reagan administration’s war by proxy with Nicaragua’s leftist government.

Maushard’s goals were few. Traveling as a freelance writer, he wanted to see how the Nicaraguans actually felt about the peace process, the Contra war and Americans.

To his credit, Maushard doesn’t feign objectivity. He believes the Contras were a creation of the Central Intelligence Agency, and the United States’ backing of this dirty little war was at best disgraceful. While no friend of the Sandinistas, Maushard seems willing to give the slayers of the brutal Somoza dictatorship the benefit of the doubt.

His reporting serves up little tidbits of information. Most Managuans whom Maushard talked to disliked the Sandinistas (no surprise considering elections in 1990 swept them out of power), were suspicious of the Contras and distrusted U.S. motives in Central America.

The book contains some interesting sketches of individual Nicaraguans. In Managua, Maushard stays with a well-heeled gas station owner named Donald, who adds color to the book. Maushard handles with skill a chapter about meeting the publisher of Managua’s spunky independent paper, La Prensa.

Maushard didn’t let reporting get in the way of his fun. The best sections of the 162-page paperback concern Maushard’s adventures with suspect food, a continuing search for female companionship, his thirst for beer and longings for a marijuana cigarette.

Maushard’s prose is simple but quite adequate. He is clearly comfortable with the written word and refrains from overwriting, a crime common to this kind of book.

In terms of history and politics, Maushard’s book is by no means complete. If you are looking for a comprehensive, historically significant first-person work on the lines of William Shirer’s Berlin Diary, Maushard’s book isn’t it.

But if an amusing and informative first-person travel piece in the mode of P.J. O’Rourke’s Rolling Stone stories appeals to you, Made in Managua is worth your time. (February 14, 1991)

Allston journalist makes it in Managua with new book by Beverly Creasey.

Allston-Brighton Journal, Boston, MA

Made in Managua, Allston native Lawrence J. Maushard’s new book, is a ramblin’ Jack Elliot account of a cocky young journalist’s visit to Managua to witness the results of the Arias peace proposal.

This “free man in a leftist state ‘o mind” reminds us that people are people no matter where you go: some are courageous, some vile. Maushard’s adventures make for edge of the seat reading. Once I started I couldn’t put the book down.

Most Americans haven’t a clue about Central America. Until president Reagan declared himself a “Contra” no one knew what side we were supporting. Even then people didn’t remember — or care. Maushard’s adventures make great copy and good history.

Maushard has the luxury as an independent journalist of going anywhere he wants to go. Judging from his first book of political observations, he leads a charmed life, entrusting his car to a family in Mexico in one episode — and finding it, remarkably, waiting for him on his way back to Boston. Maushard says he tried to make the book “both informational and entertaining…because no one wants to read dry politics.”

Maushard is a throwback to the days when a Hemingway would set out in search of a war. Since publication of Maushard’s book, he’s traveled to Egypt, aiming specifically for the Gaza Strip “because you hear lots of stories coming out of the West Bank but nothing from the Gaza Strip.” He was stopped cold at the border by Israeli guards and eventually ended up in Cairo — but that’s another book.

Contrary to popular press reports, Maushard says most Egyptians didn’t care about Operation Desert Storm. “They’re more worried about day-to-day living than any political fallout…Everyone in Egypt faces a struggle: professors, professionals and the people living in the street. It shakes you up to see women and children begging and living on the sidewalk.”

Maushard is one journalist who makes no pretense of so-called journalistic “objectivity.” He says he goes where he cares about a situation. He tries to give both sides but has “no problem” letting his bias show. Not that he can’t change his mind. “I’ll adjust my thinking,” he says, if he finds a different light on a subject.

“Just being there and reporting on it is interacting,” Maushard says. And “interacting is affecting the story. (The reporter) is part of the story because he’s involved.” Maushard proudly asserts that he’ll “let his heart hang out on his sleeve.” This is one journalist who cares. “You’re under an obligation to help — even if you’re reporting. You have to have your humanity first.”

If Americans want to get a feel for the people and the politics of Central America, unfiltered through the evening news, Made in Managua is the book to read. (August 1991)