(Appeared 6/14/17 with different headline on Huffington Post)

9066, the other WWII number which will live in infamy.

Presidential Executive Order 9066 signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942 set in motion the ethnic cleansing and desert site imprisonment of the entire US Japanese-American population on the West Coast, more than 120,000 innocent men, women and children, US citizens and resident aliens alike, for the duration of WWII.

They were finally released on numerous dates after the end of the war, left to fend for themselves with few resources in many locales still in full-blown racist mode against anyone of Japanese descent, citizens or not.

The legacy of this nightmare chapter in US history continues today, on the 75th anniversary of the first year of the internments, especially in the cities with the initial detention camps, places like Portland, Oregon.

In the wake of the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that plunged the United States into WWII, federal authorities and the US military bowed to deeply racist demands among themselves and the general public that led to these ethnically-based mass expulsions and internments.

“My brother and I, we thought we would be able to stay home and run the (family grocery) store because we were citizens. I didn’t think they would take citizens away,” Harue “Mae” Ninomiya told me during an interview in 2008. The late 1937 graduate of Jefferson High School and decades later from Portland State University clearly and pointedly recalled the episode more than six decades earlier, from the age of 89. “I knew that my mother and father being aliens would be. But what a disas . . . it was really a shock to hear that we all had to go.”

Portland was one of the 16 feeder camp locations where the specific region’s population of American Nisei (US-born children of Japanese immigrants) and resident aliens of Japanese descent (Issei) reported via city bus, vehicle drive ins, drop offs by non-Japanese friends and associates, interurban trains, or simply walking in with whatever they could carry. Their matter-of-fact bearing during the assemblage remains one of history’s remarkable displays of stoic dignity and human pride during episodes of mass oppression.

Understanding the grievous nature of its past human rights violations, Portland finally took a measure of real responsibility for these wrongs on Tuesday, March 28 of this year, 75 years after the fact, when Mayor Ted Wheeler announced that “the City of Portland aided and abetted in this (internment) process by cooperating with the discriminatory military orders applied against its own birthright citizens as well as legal residents.”

This extraordinary public proclamation about the city’s role in the internments, read by Mayor Wheeler, continued, “The City of Portland issues this official apology to its Japanese American community for failing to defend the civil and human rights of its citizens and legal residents in 1942 . . . And whereas today, March 28, 2017, Minoru Yasui Day in Oregon, that the City of Portland affirms its resolve, along with the Japanese American community, that never again will any persons be registered, restricted, or detained based solely upon their ancestry or national origin.”

“THE CITY OF PORTLAND ISSUES THIS OFFICIAL APOLOGY TO ITS JAPANESE AMERICAN COMMUNITY FOR FAILING TO DEFEND THE CIVIL AND HUMAN RIGHTS OF ITS CITIZENS AND LEGAL RESIDENTS IN 1942.”

By at least one estimate, half of the pre-war Japanese-Americans in Portland never returned after the conflict. And the once thriving main Japantown urban business and resident hotel district, located within the present Chinatown/Old Town neighborhood, completely vanished and was never reconstituted. Like it had never existed, at one time the largest Japantown on the entire West Coast.

More than following orders

Not content to merely follow orders, the City of Portland took a direct and urgent role in the internments. City Hall passed a unanimous resolution urging “immediate” removal of the Japanese-American population, revoked all business licenses held by Japanese Americans, and Mayor Earl Riley personally testified at the Tolan congressional hearings voicing the aggressive public mood urging on the pending roundup and removal of the Japanese Americans in and around the city.

According to the Densho Encyclopedia web site, the House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration (a bureaucratically bloodless term for internments, if there ever was one), commonly known as the “Tolan Committee,” held hearings in February and March 1942 in Seattle, Portland, San Francisco and Los Angeles about the pending removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast:

“The hearings began two days after President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. The Committee did not issue its final report until May 1942, so it played no official role in the decision to remove or incarcerate Japanese Americans. Nevertheless, as hundreds of people presented testimony or written statements to the Committee, it became a major conduit for those trying to influence government policy on this issue.”

Portland Mayor Earl Riley:

“I rather feel that 50 percent or more of the second generation (Japanese Americans) are loyal; but I do not think anyone is in position to ferret out the 50 percent.”

Congressman Laurence F. Arnold:

“You don’t think that you can take the chance?”

Riley:

“I wouldn’t take a chance with one.”

Mayor Riley did not mince words when the Tolan Committee visited Portland, and his testimony as the top elected official in the city remains a clear example of what the majority white elite and working class people in the Rose City were capable of:

“I hope that we shall receive orders at an early date — I would like to have them today, if possible — to evacuate all Axis aliens and second generation Japanese from this area, as soon as possible. We feel — and I think that I am speaking the sentiment of the great majority of our people — that they are definitely a hazard, and that the longer they are permitted to have the freedom that they now have, the more danger there is to themselves personally, and the greater is the hazard that is created for our defense situation.”

US Congressman Laurence F. Arnold from Illinois asked Mayor Riley at the committee hearing: “Would you care to commit yourself as to whether you think they are loyal to this country?”

Riley: “I rather feel that 50 percent or more of the second generation are loyal; but I do not think anyone is in position to ferret out the 50 percent.

Arnold: “You don’t think that you can take the chance?”

Riley: “I wouldn’t take a chance with one.”

US Congressman John J. Sparkman of Alabama inquired, “How about those who are not aliens, but are second generation?”

Mayor Riley: “That would only apply with the Japanese.”

Congressman Sparkman. “That would not apply to Germans and Italians?”

Riley: “No.”

Sparkman. “Would it apply to the Japanese?”

Riley: “Yes.”

Sparkman. “You think that they ought to be evacuated, too?”

Riley: “I do.”

Sparkman: “Even though they are American citizens?”

Riley: “Indeed.”

Mayor Riley also had a very specific recommendation for the immediate future of the Japanese Americans:

“One of your advance men asked me what I thought should be done with them. I don’t believe they should be abused. I think that they should be put to productive labor of some character, and be properly remunerated for it, so that they would be making a contribution to our defense problem. We have acres and acres and acres of beets in the interior that, for the lack of farm labor, probably will not be harvested. More acres would be planted if they had the labor. Most of these people are good at that sort of work, and I do not feel, sir, that they should be left in this area.”

And how about this for added early hardship? On December 19, 1941, less than two weeks after Pearl Harbor, Multnomah County Sheriff Martin Pratt reportedly instructed Japanese American citizens and aliens to pay their personal property taxes for 1942 in advance.

“Most historians agree that the Tolan Committee’s failure to recommend that U.S. citizens and non-citizens of Japanese descent be accorded the same rights as their counterparts of German and Italian descent represented the final capitulation of the U.S. government to the racist policy of mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans,” according to the Densho Encyclopedia.

No organized group in Portland defended Japanese Americans

“The support for removal expressed at the Portland hearings was not atypical, but the Portland hearings (of . . . the Tolan Committee) did differ from those held in San Francisco and Seattle in one important way ― the absence of organized opposition,” wrote Ellen Eisenberg in ″As Truly American as Your Son”: Voicing Opposition to Internment in Three West Coast Cities, Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 104, No. 4 Winter 2003.

“Small but organized groups opposing the removal participated actively in the San Francisco and Seattle hearings, but in Portland no organized group defended Japanese Americans or questioned the need for mass internment.”

No organized group. No one.

It appears that almost no one outside the Japanese-American community itself was willing to make a public stand in Portland against the internments ― no one except for one woman, Azalia Emma Peet of neighboring Gresham, according to Eisenberg. Only Peet, a Methodist missionary who had lived in Japan, is recorded as publicly questioning the internments at the Tolan Committee hearings in Portland.

“It will cause a serious social problem, to say nothing of taking from 85,000 American citizens their civil liberties. All this, besides causing untold suffering among our Japanese neighbors,” Peet testified in public.

“As a social worker, I am thinking of the aged; I am thinking of the sick in the hospitals today, in the Japanese community; I think of the babies that have been born since Christmas time and those about to be born; I am thinking of the young people in the schools and colleges of this State. Are they a menace to this community, that they must all be moved now? I am speaking as an evacuee, having been evacuated only last year from Japan — not evacuated by the Japanese Government, but by the American. Thank you.”

So when Portland Mayor Wheeler offered the city’s first official apology in 75 years for its role in the internments, a real threshold had been crossed. The State of Oregon made its official apology to the Japanese-American community a few weeks later on May 6, as signed by Governor Kate Brown, according to published reports.

As a social worker, I am thinking of the aged; I am thinking of the sick in the hospitals today, in the Japanese community; I think of the babies that have been born since Christmas time and those about to be born; I am thinking of the young people in the schools and colleges of this state. Are they a menace to this community, that they must all be moved now?

Azalia Emma Peet of Gresham, the only non-Japanese American to support the community during Congressional hearings in Portland.

“We hope somehow it’s healing for them to know what they endured will never be forgotten,” Nikkei Endowment Executive Director Lynn Fuchigami was quoted in local media about the importance of the official apologies for the former internees.

The Oregon Nikkei Endowment operates the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center, the Japanese American history museum in Portland, which is charged with the preservation and sharing of the history and culture of the Japanese-American community. The ONLC acts as the de facto official repository of the Portland area’s collective Japanese-American experience, with a major emphasis on the internments and their legacy.

Conditions inside the Portland Assembly Center concentration camp – from May to September 1942 – were cramped and spartan and worse. “Six cots, that’s all the furnishings there were. Six cots. No table, no chair, no nothing,” Ninomiya recalled about living quarters within the huge hall facility at the Pacific International Livestock and Exposition Center, a stockyard for cattle and other animals. She said that in their family “apartment,” the cots took up all the floor space and were simply left open side by side both day and night. “At first we got mattress bags, and we had to fill them with straw.” Mattresses were eventually distributed. As for privacy, “In our compartment, the wood partitions were, I think, 8 feet high and our doorway was a canvas bag.”

According to The Oregon Encyclopedia, a project of the Oregon Historical Society, “At one point, dysentery broke out and there was a desperate rush to use the limited toilets. One can imagine the agony and desperation suffered by those afflicted. One day, a Military Police cook came through the gate to borrow food items from the center’s kitchen. A Military Police guard shot him in broad daylight.”

June Arima Schumann, former Executive Director of the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center, said several years ago, “What they did was take away the partitions of the animal stalls, swept away the manure on the dirt floor, laid rolls of 2x4s, and then put 1×10 or 2×10 boards across to make the floor. So people lived on top of what used to be where the manure was.” She noted that a standard space for a family of four was 20×14 feet, with larger dimensions for bigger families. The canvas door coverings were purposely left several inches off the flooring, Schumann explained, “so officials patrolling the area could look into the unit.”

Groups of internees from throughout the northwest regularly came into the Portland Assembly Center as others were shipped out to their final internment camp locations. In all, four deaths and 23 births were recorded at the Portland site that held nearly 4,000 detainees, according to an Oregon State Archives exhibit. A medical facility was present, staffed by two interned doctors and four nurses.

No local media has covered the Portland apology

To date, nearly two months since it happened, no local media has covered the public apology in any serious way. No one. An important story for the major daily local newspaper The Oregonian? One would certainly think so. However, when I pointed out the event via email to Betsy Hammond, the paper’s interim politics editor, she curtly replied on April 6, “Lawrence: I would assume that previous Portland mayors also apologized for the city’s actions in the 1940s. Certainly (former mayor) Vera Katz, with her family’s history of involvement with concentration camps, would have. Am I mistaken?”

Well, yes, you are mistaken, Ms. Hammond. You most certainly are mistaken.

75 years in the making, the city’s official apology obviously stands has an important human rights watershed that should receive widespread coverage. However, to date The Oregonian has included exactly one sentence and a quote in an event preview story for the ONLC’s 75th anniversary commemorations held on May 6. The line “The city of Portland also officially apologized for its role in the incarceration for the first time in a proclamation signed by Mayor Ted Wheeler on March 28” was tossed into the middle of the May 5 article like a hidden and unexplained admission. So far, that lone single brief reference buried deep in an event preview stands as the paper’s recognition of the city’s apology. And I had to prove the first-ever status of the apology to the paper before it felt compelled to note that very simple fact.

What exactly is behind this unjustifiable lack of coverage? The Oregonian remains the local media powerhouse in Portland, it being the city’s so-called paper of record. So when The Oregonian doesn’t cover something this important, there probably has to be a reason, which in this instance might have something to do with the paper’s very own leading and reactionary campaign in support of the internments back in the day.

A newspaper’s leading campaign

The fact that a major daily editor casually assumed something of this magnitude had occurred, when nothing could be further from the truth, speaks volumes about the editorial judgment and local knowledge on display.

The campaign by the newspaper included congressional testimony by then-editor and publisher Palmer Hoyt, and The Oregonian‘s “pro-removal” editorial aimed squarely at the special congressional hearings entitled, “For the Tolan Committee” meeting in Portland the very day the piece was published, February 26, 1942. Hoyt entered the editorial into the congressional record and provided testimony to the committee.

Hoyt almost certainly wrote the removal editorial, gave it the targeted headline, published it the morning of the congressional hearings in Portland, and then sat and entered the piece into the official record while personally providing testimony at the committee session. Was this normal behavior for a newspaper and its editor/publisher?

But if that’s true, why during the Tolan Committee hearings does it appear that The Oregonian‘s Hoyt was the only representative from a non-Japanese-American newspaper or news organization to provide testimony? Combing through the hearing transcripts, I found no witnesses listed from any newspapers or radio stations or magazines in Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles, the other Tolan Committee hearing sites. Hoyt and The Oregonian appears to have stood alone in the testimony saddle. The Chandlers, who published the Los Angeles Times, did not provide testimony. Publisher George T. Cameron of the San Francisco Chronicle wasn’t spending time with the Tolan committeemen. And John Boettiger, publisher of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, did not appear. Perhaps William Randolph Hearst found the time to personally testify before Congress on such a slam dunk topic? Ah, no, he did not.

OREGON HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

“Mr. Hoyt, there was a very interesting editorial in The Oregonian this morning with reference to this particular work. Would you object to my inserting it in the (congressional) record, along with your remarks?” Palmer Hoyt, editor & publisher of The Oregonian: “No. I would be very pleased to have you do so.”

Of course, that’s not to say all the other major West Coast papers were not complicit in their own direct ways. Far from it. “As you probably know, all the major West Coast newspapers, especially the Hearst papers, advocated the internment,” Peter H. Irons, Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the University of California at San Diego wrote me via email. Dr. Irons was the lead counsel in the landmark successful federal courts campaign to reverse the internment convictions of the human rights leaders Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Minoru Yasui. Dr. Irons is author of Justice delayed: the record of the Japanese American internment cases. Middletown, Conn., Wesleyan University Press, 1989.

“I want to give you a viewpoint that I think you might be interested in, which was expressed to me the other day, and that was that 10 or 12 individuals, in the western part of Oregon when the weather is at the right point and the humidity low, and with an east wind blowing, could set a fire that would virtually destroy our entire forest area, at least the commercial aspects of it.”

Wait, what?!

That’s what he came up with, the “possibilities of sabotage” from a roving guerrilla band of Japanese Americans setting uncontrollable fires “that would virtually destroy our entire forest area”?!

During World War II, no Japanese American in the U.S., Hawaii or Alaska, citizen or immigrant, was ever convicted of espionage or sabotage, according to Densho.org.

A committee member remarked, “Mr. Hoyt, there was a very interesting editorial in the Oregonian this morning with reference to this particular work. Would you object to my inserting it in the record, along with your remarks?”

Mr. Hoyt. “No. I would be very pleased to have you do so.”

As for the most important question of the day, Hoyt’s editorial reads, in part:

“In the matter of the Japanese who are American citizens, the problem is far more difficult. It is a hard decision, in view of our traditions, to take action against men and women upon whom citizenship has been conferred. But we cannot overlook the fact that dual citizenship has been discovered in a number of instances — and America is fighting for its life. The Army will have to decide in this particular. All we can say is that the Army must not be wrong.”

The editorial leaves no doubt that it supports the “hard decision” to remove (and thereafter intern) all Japanese Americans, citizens or not. But the paper, in the end, shockingly punts and abdicates its editorial responsibility by stating the military “will have to decide in this particular.”

The Oregonian did not even have the wherewithal and the courage to clearly state its own position on removing and imprisoning innocent local US citizens. Instead, the paper incredibly deferred the question to the military, and concluded that “the Army must not be wrong.” Even though there is no doubt about the editorial position of The Oregonian, it simply can’t bring itself to go on record and write down the actual words. A more horrifying display of abdicating a bedrock journalistic editorial responsibility is difficult to find, I think.

Again, no other witnesses from any newspapers in Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles, the other Tolan Committee sites, gave any testimony. Only Hoyt from The Oregonian personally testified in front of the congressional committee in detailed support of the Japanese American removals, and offered his paper’s pro-removal editorial into the congressional record.

And so, to date, there has been no reference to the newspaper’s pro-removal editorial or editor/publisher Hoyt’s congressional testimony in the pages of The Oregonian in any internment article I can find since the internments occurred. Is that the reason the paper cannot yet bring itself today – in 2017 after 75 years – to report with any effort on the official apology by the City of Portland for its role in the internments? Because the paper would then be forced to look at the complete record of its own active role in the ethnic cleansing campaigns?

Is another possible reason the simple ignorance of its editors and staff? They apparently have no institutional knowledge about the depth and breadth of the involvement of its editorial pages as concerns the internments, or apparently even the journalistic curiosity to find out.

And hey, it’s not like these internment details are difficult to find. My own online writing on the subject goes back to 2013, largely based on the Eisenberg scholarly article in the Oregon Historical Society magazine originally published in 2003, and still easily available online.

Recently, The Oregonian has attempted to deal with its internment past, especially in a Feb. 19, 2016 article by Joseph Rose (Japanese-American internment in Oregon: Never forget February 1942) that claims the paper’s coverage at the time was “appalling,” due to its inability to ask “no hard questions. The newspaper failed to perform its basic function of fostering debate, seeking the truth and questioning authority when human lives hang in the balance.”

What’s really appalling is either Rose knows the truth, or he’s failed to make the most basic efforts at learning the role taken by his employer in this cruel human rights chapter. Either way, his 2016 article fails to recall that The Oregonian not only did ask and respond to some important internment-related questions of the day, it took a leading role early on in the roundup of the Japanese-American community both through its editorial pages and in person by its publisher during congressional hearings on the internments held in Portland.

The paper even printed front page national and local articles on Feb. 25, 26 and 27, 1942 before, during and after the congressional internment hearings in Portland, but this critical coverage where the publisher’s own testimony is referenced isn’t mentioned by Rose. He notes only that an April 1942 internment camp piece is buried on page 17, and how state authorities “debate how they should use farms ‘evacuated’ by families with Japanese ancestry, as if the owners had a choice to leave the land on which they raised crops and American legacies.”

These are the two items cited by Rose as “appalling” examples of journalistic internment malfeasance in a piece titled “Never forget February 1942”?! Not the quality of the coverage of the special Tolan congressional committee internment hearings held that month in Portland, and publisher Palmer Hoyt’s personal testimony? Stories that made the front page on consecutive days in February 1942? Instead, he choose that an internment camp article only made page 17 two months later, and an undated piece about state officials casually debating the potential use of former Japanese-American land?

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

The Portland Assembly Center detention camp held thousands at a former stockyard from May – September 1942: “What they did was take away the partitions of the animal stalls, swept away the manure on the dirt floor, laid rolls of 2x4s, and then put 1×10 or 2×10 boards across to make the floor. So people lived on top of what used to be where the manure was.”

Wouldn’t serious reportage on the topic involve a look at the paper’s potentially “appalling” front page coverage of the special congressional internment hearings held in Portland, which included the personal testimonies of the paper’s publisher and Mayor Earl Riley? This was something to completely ignore?

The second Oregonian article of recent note internment-wise was the mistitled “He was born in Portland. An executive order sent him to a Japanese internment camp” on February 17 of this year by Casey Parks, which was fine regarding the internee account. But the article contained nothing about the leadership role the newspaper displayed in the internment campaign, or the similarly horrific role of the city government. Nothing.

When I pointed out these glaring omissions that only help to whitewash the role of Portland’s municipal government and the main media outlet, her newspaper, I received the following reply on Facebook from Parks: “Lawrence, thank you for your comment — repeated about 40 times across the Internet today. This wasn’t an attempt to whitewash. I didn’t know about the city of Portland (emphasis added). But I do feel like I showed that the majority of people were complicit here — I even quoted a pretty awful Oregonian article. We also showed Oregonian headlines with the racist ‘nicknames.’ I feel like that shows pretty well that the general public, and the newspaper included, don’t have a good record on this. As for publicly apologizing, that is not up to me. Feel free to reach out to the editor of the paper to ask about the possibility of that. In the meantime, I will keep sharing the stories of those who have been disenfranchised/discriminated against/marginalized in hopes that Portlanders will know this history.”

I replied, “No one is questioning the need to share the stories of the disenfranchised and marginalized. And no one is asking you personally to make any apologies. Why do you think that? What you continue to fail to understand is The Oregonian specifically led its own extraordinary campaign for internments, in printed explicit editorials and in the personal actions of its publisher/editor, not just a few scattered articles. I think that undeniable overarching effort qualifies as something immeasurably more than not having ‘a good record’ on internments. You don’t get that?! The newspaper helped lead the campaign for mass internments far beyond what you chose to recall. Were you even aware of the ‘For the Tolan Committee’ editorial and the congressional committee appearance of publisher/editor Palmer Hoyt? Also, you absolutely should know what the City of Portland did against the Japanese-American community in the name of the majority of its people. How can you state ‘I didn’t know about the city of Portland,’ like it’s not the job of a reporter writing about an internee to know the city’s specific legislative and other actions on this topic? Was that too much work for you? My God. I can’t believe you made this admission and somehow think your story is in any way adequately covered. This is a major local story still playing out over decades that you failed to address in a way that clearly displays the breadth and depth of official Portland participation in arguably the greatest example of local systemic racism that resulted in an actual ethnic cleansing of an entire minority community.

Parks did not respond.

Her article should have been been headlined “He was born in Portland. An executive order — backed by City Hall and this newspaper, among other local institutions — sent him to a Japanese internment camp.”

And if Parks really is serious about wanting to “keep sharing the stories of those who have been disenfranchised/discriminated against/marginalized,” it might be beneficial to actually identify the main agents of their oppression if the goal is “that Portlanders will know this history.”

If it needs a motivating example, The Oregonian would do well to look at the editorial pages of the Los Angeles Times, which on Feb. 19 this year declared “75 years later, looking back at The Times’ shameful response to the Japanese internment” and in the text, “That was another time, and another Times. This newspaper has long since reversed itself on the subject. Not only was some of our reasoning explicitly racist, but in our desperate attempts to sound rational — by supposedly balancing the twin imperatives of security and liberty in the midst of World War II — we exaggerated the severity of the threat while failing to acknowledge the significance of revoking the most fundamental rights of American citizens based solely on their ancestry.”

But is it an actual apology if one doesn’t use the word?

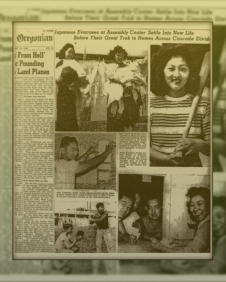

During the middle of the war, 1943 to be precise, Palmer Hoyt was appointed by FDR as director of the Domestic Branch of the US Office of War Information, the American WWII propaganda agency. He reportedly served in that capacity for six months. Perhaps the federal government noticed pages in The Oregonian like those of May 3 and 10, 1942 showing smiling happy and attractive Japanese Americans reporting to the assembly center, playing baseball, gathering laundry, and getting together with friends, all while being held behind barbed wire manned by armed US soldiers in their hometown concentration camp! Well, they neglected to show the barbed wire and armed guards, as one might expect. Talk about war-time propaganda.

After the war, Mae Ninomiya returned to the Rose City from a large concentration camp in Idaho and restarted their Lombard Food Center grocery business at the corner of Denver & Lombard streets in the North Portland Kenton neighborhood. Ninomiya said hers was one of the only Japanese families in the Kenton neighborhood remaining after the war:

“Oh, yeah, there were bad reactions for quite a while. It took us quite a long time. Quite a while. Because the neighbors said we were enemy aliens and such. That they shouldn’t be trading with us. So it took a while.”

Old customers started returning to the store because of the high quality of the produce, but usually only after nightfall. During the day, pedestrians would go so far as to walk across the street rather than pass by the store, Ninomiya remarked. “I felt like a monkey in a cage.”

According to Densho.org, what would become known as the “Redress Movement” took flight in the 1970s and led eventually to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided a presidential apology and $20,000 payments to surviving former detainees. Also during the 1980s, the discovery that the federal government had consciously withheld information about the military necessity of mass removal from the Supreme Court in 1944 led the wartime defendants to seek to reopen their cases, resulting in their convictions being overturned.

At the very least, the remaining former internees deserve a full accounting of the actions by The Oregonian during the internment campaign in the current pages of the newspaper. Journalistic integrity demands nothing less than a comprehensive investigation, as well as a genuine apology in its Op-Ed pages more than seven decades late but still as necessary as ever.